Alum Restores Order After Archival Relocation

By the Rev. Kyle Oliver

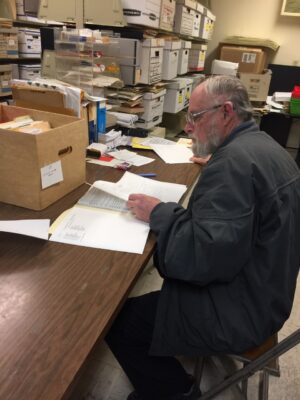

When the Rev. John Rawlinson (MDiv ‘70, PhD ‘82) contacted CDSP in hopes of accessing the archives, he didn’t expect he would eventually be managing them.

Rawlinson was seeking access to papers and other materials from one of his former professors, the Rev. Massey Shepherd, PhD (DD ‘85). The world-renowned liturgical scholar taught full-time at the seminary from 1954 until 1981.

“Eventually I was told, ‘The reason you can’t see them is that you won’t be able to find anything,’” Rawlinson said. “So I offered to organize them.”

Rawlinson is a trained historian with a doctorate from the Graduate Theological Union (GTU) and had served as archivist for the Diocese of California for twenty years. He received permission from CDSP to tackle the forty-seven-box collection, slowly cataloguing Shepherd’s papers and other materials over the course of more than two years.

At the end of the project, CDSP agreed with Rawlinson’s assessment that the Shepherd materials were important enough to the Episcopal Church as a whole to be sent to the denomination’s archives in Austin, TX.

“That project gave [Dean Richardson] a close intimate knowledge of what I had done and how I had worked. Based on these impressions and the recommendation of the Episcopal Church archivist, he decided it would be OK for me to stay on.”

The new role of CDSP archivist expanded Rawlinson’s purview to the seminary-wide collection, which had been moved during a reconfiguration of campus spaces. I asked him how he approached the process of getting to know the material.

“You don’t start with a box,” Rawlinson said. “You start with a mass, in this case of 150 boxes’ worth of material. The first issue is asking ‘What’s here?’”

In the roughly two years since he became CDSP’s official archivist, he has taken more than thirty-nine handwritten notebook pages’ worth of inventory: faculty meeting minutes, board minutes, notes from curriculum planning, descriptions of student activities, faculty writing, administrative records, fundraising records, GTU records, and more. The work before him recently expanded when CDSP staff identified additional archival records filling nine file cabinets and more than forty boxes.

“The next step is asking, ‘How do I organize it? Based on this inventory, what are the categories?’” Rawlinson said. “Sometime during my training as a historian, I learned there’s a significant difference between an archive and a library. In a library you try to pull together all the items on the same topic. In an archive, you’re putting together all the materials that were created by a person or office.”

Of course, some of those offices find themselves embroiled in conflict from time to time. One particular piece of controversy Rawlinson explored involved a bit of Berkeley history he remembered from his student days but about which he had lingering questions: the protests, and eventual deadly confrontation with law enforcement, connected to the 1969 creation of the People’s Park on UC Berkeley property.

“The incident began not at the university but at the Baptist seminary,” Rawlinson recounted. “They had a class on social ministry, and the professor sent them out to interview people in the neighborhood about what the city needed, and person after person said, ‘We need a park.’ So these students started building, and others, including from my class, started joining in.”

Rawlinson thought he had heard that, after the violence of May 15, Dean Sherman Johnson had used seminary money to bail some CDSP student protestors out of jail. But he had a hard time believing that the trustees would have rubber stamped such a decision.

“When I was working in the archives,” Rawlinson said, “I came upon the memo he sent to the trustees confirming the use of school money to bail those students out of jail. He wrote, ‘I believe the government has the right to manage their own property, but I believe the government use of authority was unwise. Our students were there to monitor and serve as medics.’

The trustees didn’t boil over. They took Dean Johnson’s word, and that was that. His memo was an important piece of the puzzle.”

While not every item in the archive is connected to such significant moments, Rawlinson says there is

much to learn from the collection, and he welcomes collaborators.

“Early on, it had to be a one-person job,” he said. “Somebody has to design the basic system. Also important at the outset was to have some sense of what, if any, highly confidential material was there, because it may be that certain areas have to be off limits. But that time has passed.”

He notes that in addition to the possibility of supporting independent research, volunteering in the archives has value as professional development:

“One of the requirements of the canons of the Episcopal Church that is almost always ignored is that the

priest in charge of any congregation i responsible for organizing and retaining the essential materials to maintain a congregational archive.”

Students and alums, take note.