A Rugged Journey Home

By Kathleen Moore ’19

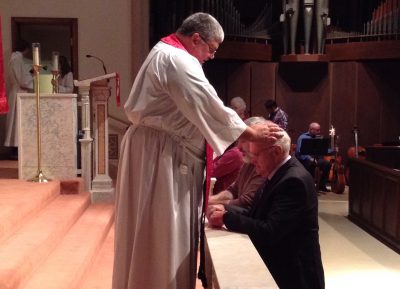

Tim Dyer ’19 already knew a great deal about the power of Christian community before he stepped foot on CDSP’s campus.

A host of life challenges, including a near-death experience in 2012, threatened to thwart Dyer’s dream of attending seminary. Not only did he overcome these challenges, he brought what he learned from them to his studies and his ministry.

Dyer currently serves as associate vicar at Trinity Memorial Episcopal Church in Warren, Pennsylvania, and St. Francis of Assisi Episcopal Church in Youngsville, Pennsylvania, where he has deep roots.

“My family generally didn’t attend church until I was about 12 years old,” Dyer says. “My dad was an alcoholic, and as part of his recovery he started to attend St. Francis.”

Dyer served as acolyte and was involved in many aspects of parish life until he graduated from high school. Then he headed off on a journey that began with Marine Corps boot camp, and took some agonizing twists and turns before leading him back to two small communities on the edge of the Allegheny National Forest about 50 miles southeast of Erie.

“My story may seem extraordinary, but I think every one of us has an extraordinary journey, and I think it’s important to recognize struggles in ourselves and in others,” he says. “And in doing so, we recognize Christ in one another.”

In addition to serving two congregations, Dyer has encouraged interfaith dialogue in rural Warren County and its environs, founding the Children of Abraham Project in 2012. At commencement in May, he was given the Episcopal Preaching Foundation Award, which is presented to the CDSP student who has demonstrated the greatest improvement and aptitude in preaching. The prize, which is sponsored by the foundation, is awarded by the dean and faculty.

“When they called my name I couldn’t believe it,” Dyer says. “And then to hear that the person selected for that award is one that is selected by the faculty — I was blown away. I am so humbled.”

Finding his way back to church not only gave Dyer purpose and direction, it may well have saved his life.

After graduating from basic training in 1985, Dyer was stationed in Rota, Spain, when

his longtime girlfriend broke up with him, unmooring him in new and unfamiliar surroundings. “Being away from my church, I felt that I had no foundation,” he says.

Looking for a way to numb the pain, Dyer turned to alcohol. “I stayed drunk for most of the time I was there,” he says. “It was nothing for me on a day off to get a bottle of Jim Beam in the morning, drink that and then go out that night and party. It was a pretty low time. I was angry at God, I blamed God for it. I can’t tell you how many times I cursed him out.”

Two years later, Dyer was transferred to Twentynine Palms, California, where he severely injured his knee. “And the only thing the Marine Corps would give me for that was Motrin, which didn’t cut it,” he explains.

One night, Dyer met a woman at a bar, and told her about his pain. “And she said, ‘I’ve got something that will take care of that,’” Dyer recalls. “And she pulled out this little baggie. It had crystal meth in it. So she and I became an item, and I started doing crystal meth.”

By the time Dyer quit using methamphetamines, the formerly strapping Marine weighed just 145 pounds. “There was nothing left of me,” he says. “I had OD’ed a couple times. I had come to the realization that doing these drugs was killing me.”

Even after getting clean, Dyer remained distant from his family while living in Sacramento. “I was too embarrassed to go home,” he says. His parents, meanwhile, had remained heavily involved in their parish and in the diocese, and had been praying that he would come home and find his way back to God.

“That took quite a while,” Dyer says.

His return was set in motion by a phone call from his mother telling him his father had suffered a heart attack and might not survive. Dyer couldn’t afford a bus ticket, but his parents sent him money and his boss at Rent-A-Center chipped in the rest. “He didn’t loan it to me,” Dyer says. “He gave me that money. And I got on a bus and came home. I felt very much like the prodigal son. It was overwhelming, the way they welcomed me back.”

Once he settled back into life in Pennsylvania, Dyer reconnected with Noreen Jones, the first woman he had ever dated. They married in 2001. “We went to the priest at St. Francis, Mother Marilyn Thorssen,” Dyer says. “We’d only been in there a couple times, and I asked her how much the church charges for someone to get married there. And she said, ‘Well it’s interesting you ask that question, because if you’re not a member it’s $500, but if you are a member, free.’ So we became members.”

The Dyers became involved in the life of the parish, and when Thorssen was diagnosed with cancer, Tim found himself filling a leadership role that continued after her death. “It was several years before they got another priest,” Dyer says. “And it seemed that no matter what Sunday it was, it was always Deacon Michael Bauschard and I serving together at the altar.”

Eventually, Dyer told Bauschard he was feeling a call to ordained ministry. “He looked at me and said, ‘What’s taken you so long to tell me?’” Dyer remembers. “It was something that he saw in me.” After entering the ordination process, Dyer learned he needed to get a bachelor’s degree, and he enrolled as an online student at Clarion University in western Pennsylvania in 2008.

His life was back on track, and then it wasn’t. On a November morning in 2012, Dyer was on his way to work, when a car traveling in the opposite direction hit a deer, launching it into the air, and through Dyer’s windshield. The deer’s body struck him in the face. “The next thing I know, my truck is bouncing around,” he says. “I thought I was going through a field, but I was going down into a ditch and into a creek. My jaw was hanging to the side. My arm didn’t work.”

Dyer was airlifted to a hospital in Erie, and as he was being wheeled into the hospital, he caught a glimpse of himself on a reflective surface. “My face was nothing but blood,” he says. “They wound up totaling my truck not because of the damage, but because there was so much blood inside the truck it was a biohazard.” Even with the extent of his injuries, Dyer spent just a week in the hospital before being discharged.

Soon after arriving home, however, he collapsed on the floor and was sent back to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with endocarditis – an infection of the lining of the heart. “My body was shutting down,” he says. “They sat my parents and Noreen down around Christmastime and told them I had a 20 percent chance of living. And they asked if they were prepared for me to die. They were not expecting me to pull through.”

The most difficult challenges he faced were not physical. “Not being able to breathe, that’s a horrific feeling,” he says. “Not knowing where your loved ones are or what’s going on, that’s a horrific feeling. But the worst feeling that I had was that I had no connection with God. That was the most frightening thing in the world. I had no sense of spirituality. The words Jesus said on the cross, ‘Why have you forsaken me?’ Boy that just rung home with me, that feeling of abandonment.”

Heavily medicated, Dyer could not read and turn to things in which he usually found reassurance, such as the Book of Common Prayer. “And that’s where I learned what it really meant to be in a Christian community,” he says. “It was the diocese, the people that came to visit me, the people that prayed for me who got me through. It’s still very powerful.

“As it turns out, I beat the odds. It took a lot. I had to learn to walk again, I had to learn to talk and eat. I had to rely on this community. I had to have faith and trust in God in Jesus Christ and the love that these people have. My wife supported me. The diocese supported me. Bishop Sean [Rowe of the Diocese of Northwestern Pennsylvania] supported me.”

After he was discharged from rehabilitation, Dyer graduated cum laude from Clarion with a bachelor’s degree in liberal studies and a minor in psychology. He tried returning to work, but was physically unable to do jobs he’d done in the past. “The only thing I could find around here was $9 an hour and for someone that owned their house, you just can’t do it,” he says. “So I owe it to Bishop Sean and the diocese for thinking outside the box and offering me an opportunity that normally isn’t presented to someone being sent to seminary. I was allowed to work as clergy for the church while working toward my degree.”

When it came time to consider a seminary, Dyer felt CDSP was the natural choice. “CDSP was offering a low-residency program, which to me is also thinking outside the box,” he says. “The traditional setup for going to seminary, spending the time there, it doesn’t function for everybody.” Having studied online for his undergraduate degree, “the sense of community that developed online at CDSP was very familiar.”

The lingering effects of the accident made life on campus a challenge during summer and January intensives. “It actually hindered me from doing things with people,” he remembers. “People liked to get out and hike around the area. Well, it kicked my butt walking back up from Euclid [Avenue]. And then being there with my heart condition, it’s difficult to eat healthy. So, my past experiences influenced how I was at CDSP, even getting to class was challenging with all the stairs.”

Dyer was particularly grateful for the support he received from faculty members who were aware of at least some pieces of his past struggles and current condition. “I have abiding respect and love for the concern [academic dean] Ruth Meyers showed,” he says. “Susanna Singer was my adviser. She knew quite a bit and was very caring. Andrew Hybl went out of his way to ensure that room accommodations for me were on the first floor, which was a huge help.”

Dyer says what he learned in classes was complementary to his hard-won life lessons. “I do have all these life experiences,” he says. “Well, Ruth’s classes on liturgy gave me resources I’m able to pull on to celebrate or mark things like that, these changes in life.”

CDSP’s place within the Graduate Theological Union was particularly valuable to him, he says. “A couple of the last courses I took were through Starr King School for Ministry, and there were people with huge differences of belief,” he says. “And to be able to communicate and validate their opinions even though I may not believe them or endorse them … you still find the common thread that connects it.

“The sabbath class with Naomi Seidman (at the Richard S. Dinner Center for Jewish Studies) was incredible. We went to a Jewish synagogue for sabbath, and it was one of the most powerful spiritual experiences I had at CDSP. Just hearing the ancient language mixed with modern music, it seemed to open a portal between worlds. It was incredible.”

He attributes his success to his community in Northwestern Pennsylvania and the community at CDSP. “These professors, they cared. Everyone along this path, I’m grateful for them. My journey is a community. I came from roots that you would never consider being a priest. Yeah, I had work to do, but it was community that helped me, all the communities I encountered during my journey.”